The coupling of the

legendary artistic genius and his brazen muse became a stereotype

long before art became a commodity among the bourgeoisie. Most

Renaissance artists were driven inventors and rarely had time for

conventional propriety. And in those days, there was no Media to tattle on a celebrity...

Art in “Western”

culture has always been a pissing match, with each artist having to

outdo the other. The egos involved, the controversies, the gossip and

mischief of the competing collectors and institutions made an

intoxicating and sometimes toxic brew which somehow inspired

creativity and patronage, for whatever reasons. Whispers and public

assumptions and outright lies about artists and their private lives

fueled the fires of art commerce, and without them artists would have

starved even worse. Art is just an expression of the Philosophy of the Age... or so I was taught in Art School. And so every artist's muse is just the embodiment of his philosophy...

There is no way to gauge the importance of the artist's muse, but we can assume from the paintings and the histories cherished in art schools that they became the soul of most galleries and every art museum.

There is no way to gauge the importance of the artist's muse, but we can assume from the paintings and the histories cherished in art schools that they became the soul of most galleries and every art museum.

Every artist has to have a

passion for something which drives him... to create, to perfect his

craft, to endure the financial chuck holes in the art market, and for

many artists that essential quest was... women. Mary the Mother of

Jesus may have been the first muse, quickly followed by the Greek

goddesses. It went rogue from there, until prostitutes and courtesans

dominated the excitement in European studios. And that is where we

will start this snipit of art trivia.

Rembrandt was perhaps the

most ribald of the Dutch painters, who took his cue from the

non-conformists like Rubens and the risque Dutch school. Rubens

painted the most fleshly of females in wild sexually-charged

situations. If Rembrandt was to compete, he had to eventually use

female models and paint them without shame. His wealthy blond muse

Saskia, introduced through his art dealer, modeled regularly for him

and then became his wife. This somewhat legitimized his untold hours

devoted to studying and illustrating her form. He painted her as a

man infatuated, if not madly in love with her countenance. Through

his paintings she became an infamous woman in Holland... for a time.

But Saskia became fatally ill after their fourth child was born, and

Rembrandt began to take unusual risks during her illness by painting

Geertje Dircx, his child's wet nurse, in the nude. After Saskia

passed away, and he refused to marry Geertje after an extended love

affair, she sued him for breach of promise- and won. The

court-mandated alimony he owed her was negated however when he proved

that she had stolen and hocked some of Saskia's jewelry. She was

committed to an asylum, for twelve years, ending his first scandalous

affair, and beginning the much celebrated ill-fated artist's muse

stereotype.

Not discouraged, Rembrandt

took another concubine, Hendrickje, who was a true “bohemian,”

satisfied to cohabitate with him without the benefits of marriage.

She became pregnant, and after she was interrogated by church

authorities in 1654, Rembrandt was banned from the sacraments of the

church for living in sin.

Later poor maligned

Geertje was released from the asylum and still determined, sued

Rembrandt for false imprisonment. It became obvious after Rembrandt

took in Hendrickje, that it was nothing personal, but he would not,

could not marry anyone under any circumstances. His first wife, now

deceased, had left him as trustee of her wealth, and well fixed, he was

able to support himself and his son nicely, but his financial support

was only made available to him as long as he remained single. To

avoid losing Saskia's inheritance, he could not marry again, but

after his son came of age, he still eventually went bankrupt.

To protect Rembrandt from

his debtors, Hendrickje opened a gallery and managed his art career,

making him a sequestered laborer and his concubine his veritable

overseer... until she was killed by the plague in 1663. Scandalized,

sued and banished by society, Rembrandt spent his last days

impoverished and humiliated.

This mess was a warning

for all artists of the future, and it was absolutely ignored. The

demand for nudes in art made models a necessity, and the temptations

and improprieties which came with them became an accepted part of the

business. By the time these next models came on the art scene, hardly

an eyebrow was raised...

The star of the blockbuster play Mazeppa, Adah Menken, the

Victorian version of Madonna, had

joined an elite bohemian family of emerging artists and intellectuals

who networked between New York and London and Paris and became the

European's favorite American pet. In England she was escorted in the

markets by Dante Rossetti, James McNeill

Whistler and others who were soon to become

famous in their own right. Rossetti, a writer and painter, respected

her poetry, and along with his brother was somewhat responsible for

establishing its status and publishing her abroad.

Rossetti

also endorsed and promoted the writings of her mentor, Walt Whitman.

No doubt the fellow

American, James Whistler welcomed Adah as a ready associate, and it

would not have been absurd for him to have asked her to model for him

during that time. After all, she had no modesty... and she was

considered to be very attractive.

My tintype of Adah Menken

Charles Howell,

a friend of the artists and a natural-born huckster, connected Adah

with the rising star in British Literature, Algernon Swinburne. Soon

Adah saw in Swinburne the talent necessary to polish her poetry and

to complete her autobiography, something even Mark Twain had declined to do. What evolved was an amazing flow of

synergy, where each person freely and shamelessly used the other. The

greatest need for all of these creative types was inspiration. Each

gave what she or he had to enable the other. For artists, nothing

could be more inspiring than a beautiful model. A muse. Since many models

ended up being the artist's lovers... well you can imagine. And no

one gave more inspiration than Adah.

For comparison... Mine (center) must have been made

fairly early, when she was in Texas or Ohio

fairly early, when she was in Texas or Ohio

Beautiful Rosa

Corder, a fledgling artist and Charles

Howell's girl friend, (and a prolific forger of Rossettis!) did a

little modeling as well. Later she would move back to the U.S. and

model for James Whistler after Howell was found murdered in a New

York gutter. This was a fast crowd... as in "two kinds... the quick and the dead."

It

has never been suggested before... but I believe

Adah Menken not only ran with a the fast crowd, and thrilled the masses and stimulated British writers, but may well have

modeled for artists while in Europe. All while acting as

a Confederate agent. She had stormed European shores in 1864,

fleeing the devastating results of the South's War of Secession, and

any appearance of complicity she may have had in the Confederate

cause. She needed money and friends, and found a ready home with the

Pre-Rafaelites and other British liberals. There was a yet undefined

affinity between the Southern “Cause” and some British subjects.

Certainly Confederate ships were being built in British shipyards

when Adah arrived, and she would have known about them, through her Confederate spy network.

In fact, James Whistler's brother was a trusted Confederate officer, soon to be sent to England with cash to arrange financing for the ships under construction. Adah's plan may well have been to supplement the “Cause” with funds she raised in Europe, just like she had done with her tour through California and the west. Meanwhile she had a wild time. In fact it would be a surprise if she had not posed for some of these lusty, counter-cultural creatives. It makes perfect sense, and I believe my artist's eye has found perfect proof.

A mischievous provocateur, Menken used her trade

as a cover for her rebellious Southern leanings.

Dr. William Whistler.

In fact, James Whistler's brother was a trusted Confederate officer, soon to be sent to England with cash to arrange financing for the ships under construction. Adah's plan may well have been to supplement the “Cause” with funds she raised in Europe, just like she had done with her tour through California and the west. Meanwhile she had a wild time. In fact it would be a surprise if she had not posed for some of these lusty, counter-cultural creatives. It makes perfect sense, and I believe my artist's eye has found perfect proof.

It is known that between

her flamboyant affairs with British men of literature, Adah frolicked

off to France with Gustave Courbet at one point. Perhaps one of the

British artists had been doing too much bragging about their secret mother lode of inspiration, the American sensation who appeared to ride a horse on

stage buck-naked... and Courbet in typical style seized that which

he- and Art- and all bohemian/socialist/humanist culture must have.

Whatever the case, there are several paintings done by Courbet which

suggest that Adah Menken left a silent yet groundbreaking visual

legacy in French art.

Gustave Courbet was a sort

of eccentric uncle to the Impressionists. He was undoubtedly the most

adventuresome of the French artists, unafraid of breaking conventions

or offending the masses, and even eager to do so. And who else to

recruit to pose in his daring compositions, than the most daring

entertainer of his time? Here is uncanny visual evidence that Menken

left a lasting legacy beyond her tacky skits in Europe. As many as FIVE paintings, all by Gustave Courbet, and one perhaps his most famous,

suggest that Adah Menken was front and center for at least a short

time in his Paris studio... a place fitting her reputation, where art featuring the most

unconventional and risque subjects was being created: The equivalent to, or even superseding her sensational displays on stage, in oils on

canvas... and even beyond, on the Internet today!

Gustave

Courbet: Woman With A Parrot- 1866. Through the help of American artist Mary Cassatt, this painting ended up in Louisine Havemeyer's famous art collection, now housed at the MET.

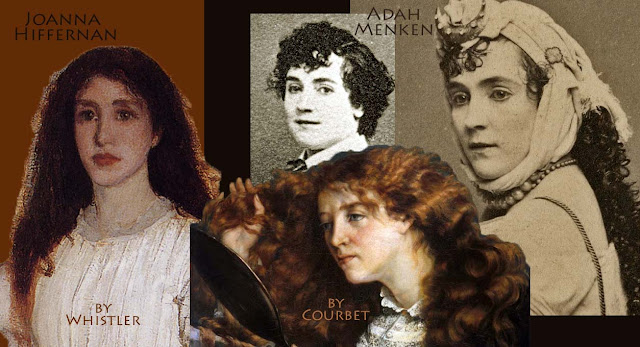

Joanna Hiffernan as Whistler saw her, on the left.

As Courbet supposedly saw her, bottom center.

Photos of Menken above and right.

Sorry, but auburn-haired Joanna Hiffernan was slender and long faced, with a neck like a gazelle, and too petite and pretty to be the nude above: the supposed portrait of her at the bottom (in pic above) by Courbet suggests that she had a shorter neck, a small forehead, and sunken, down-slanted eyes. All physical contradictions to Whistler's Jo. Courbet's Jo has somewhat thin misfitting lips, Whistler's has extremely full lips. All of these inconsistencies lead to my doubts, and then the face of Menken compared to several of Courbet's subjects truly rings a bell.

I suggest that Courbet's redhead above was at best an amalgamation... not completely a painting of Hiffernan, who was a sort of scapegoat for Courbet's mixed bag of muses, and the painting was actually just a bad portrait of... Adah Menken. Compare the same likeness below, with several Courbet studies.

It seems what Jo Hiffernan contributed most to Courbet's female subjects was her hair! Being Whistler's former flame and model, she might well have known Adah, and no doubt did model for Courbet, perhaps in "Origin of the World," where he cut off her head, showing only her torso... in the most "unlady-like" portrait done in French history. You will have to search that one on the Internet yourself... And she may have been featured in “Sleep” (1866), a highly suggestive work that may have been the first nude lesbian love scene, which featured her and someone else...

Menken assumes a familiar pose.

A

black haired, shameless fleshpot, famous for posing in dreamy,

horizontal ecstasy...

Adah

may have starred in Courbet's "Sleep" as well. Most researchers believe Adah was

at least bi-sexual, from the content of her private correspondence.

If Courbet was painting such subjects, were homosexuality and

bisexuality not becoming a hot topic among these European elites?

Is it possible that Adah Menken, the seemingly amoral entertainer,

was also at the vanguard of bohemian culture and its various

expressions?

This could inspire a new, totally different interpretation of "Sleep," Courbet's historic flirtation with pornography. This will get deep, but it may be that this suggestive figural had less to do with lesbianism, and was more an edgy artistic exploration into the sub-conscious. My study of Menken and this painting have come together into one theory, that Adah Menken, artist, singer, equestrian, actress and poet, was on a bizarre crusade to define modern womanhood, and hopefully herself in the process. Only a few people close to her knew that she was not only bi-religious (Christian and Jewish) and bi-sexual, but bi-racial. A dark-eyed New Orleans "Quadroon," Adah had used toxic lead-based pigments to lighten her skin for years. Like the painting, there was a light Adah and a dark Adah... She always wore wigs to appear as a blond or brunette, but her hair was naturally almost black, and extremely curly. She had spread so many lies about her origins and her life story that nobody really knew her very well. She was, as I think this painting by Courbet so tenderly illustrated, living the lives of two distinct people.

Menken was the premier star of her day, and Courbet considered himself her equal in art. As they grew close, and talked, I have no doubt that at some point Courbet envisioned the impossible: A portrait of Menken's inner dilemma and the simple complexity of it; a woman playing many roles, who stepped off of the stage to be the International star, which was just a front for a woman of color, passing for white, whose mother had been a slave. It was only at night, IN HER SLEEP, that Adah Isaacs Menken met up with little Berthe Theodore, and they became one.

It was the only time, in her sleep, that Adah felt complete, safe, and truly herself. The more famous she became, the more precious those hours became to her... until she finally succeeded in her desire to finally become one again, by committing suicide. She was never returned to the States, buried temporarily in a pauper's grave, but her split existence was beautifully captured forever in Courbet's masterpiece.

That is what I think "Sleep" is about. Courbet loved her, and loved the attention the painting got for him, and I think he loved the fact that nobody knew what it was all about! And they could never... In the free-thinking world, Adah's body was mere temporal flesh, something to be celebrated, but Adah's public personna, something she had shaped like a sculpture, was to be honored and protected. In a strange way, Coubet held to his own concept of ethics and morality, and it was not without a kind of integrity, albeit salvaged from pre-christian times.

For the immediate years after her death, Courbet appears to have been obsessed with this great creative genius, and he devoted himself to several tributes to her... If I am right!

This could inspire a new, totally different interpretation of "Sleep," Courbet's historic flirtation with pornography. This will get deep, but it may be that this suggestive figural had less to do with lesbianism, and was more an edgy artistic exploration into the sub-conscious. My study of Menken and this painting have come together into one theory, that Adah Menken, artist, singer, equestrian, actress and poet, was on a bizarre crusade to define modern womanhood, and hopefully herself in the process. Only a few people close to her knew that she was not only bi-religious (Christian and Jewish) and bi-sexual, but bi-racial. A dark-eyed New Orleans "Quadroon," Adah had used toxic lead-based pigments to lighten her skin for years. Like the painting, there was a light Adah and a dark Adah... She always wore wigs to appear as a blond or brunette, but her hair was naturally almost black, and extremely curly. She had spread so many lies about her origins and her life story that nobody really knew her very well. She was, as I think this painting by Courbet so tenderly illustrated, living the lives of two distinct people.

Menken was the premier star of her day, and Courbet considered himself her equal in art. As they grew close, and talked, I have no doubt that at some point Courbet envisioned the impossible: A portrait of Menken's inner dilemma and the simple complexity of it; a woman playing many roles, who stepped off of the stage to be the International star, which was just a front for a woman of color, passing for white, whose mother had been a slave. It was only at night, IN HER SLEEP, that Adah Isaacs Menken met up with little Berthe Theodore, and they became one.

It was the only time, in her sleep, that Adah felt complete, safe, and truly herself. The more famous she became, the more precious those hours became to her... until she finally succeeded in her desire to finally become one again, by committing suicide. She was never returned to the States, buried temporarily in a pauper's grave, but her split existence was beautifully captured forever in Courbet's masterpiece.

That is what I think "Sleep" is about. Courbet loved her, and loved the attention the painting got for him, and I think he loved the fact that nobody knew what it was all about! And they could never... In the free-thinking world, Adah's body was mere temporal flesh, something to be celebrated, but Adah's public personna, something she had shaped like a sculpture, was to be honored and protected. In a strange way, Coubet held to his own concept of ethics and morality, and it was not without a kind of integrity, albeit salvaged from pre-christian times.

For the immediate years after her death, Courbet appears to have been obsessed with this great creative genius, and he devoted himself to several tributes to her... If I am right!

Gustave

Courbet: La Femme A La Vague,

aka "A Woman in the Waves," or

"The Bather"- painted in 1868-

Featuring the profile of Adah Menken.

The breasts were someone else's!

"The Bather"- painted in 1868-

Featuring the profile of Adah Menken.

The breasts were someone else's!

Once

again, the near exact face AND body type of Adah Menken in A Woman In The Waves. Once again, Hiffernan

may have modeled her hair. But the face could certainly have passed among her admirers as a final tribute to Adah Isaacs Menken. In the beginning, perhaps the

artist was infatuated, INSPIRED, and unafraid to paint her as she

was... after all, she planned to eventually go back to the States...

thus there was no local or regional reputation to protect. In fact

Menken, a Victorian “candle in the wind,” was already dead when

The Bather was debuted.

If

you read the story of Menken, you understand how integrated she was

with the creative forces in England and France. It seems she was

striving for a sort of artistic triple crown, doing her necessary

melodramas to finance her writing, and desperate Confederate naval

plans which nnever materialized. While loving up Swinburne and Dumas and others to glean

whatever she could to establish her literary foundation, she may have been secretly

posing nude for the most prominent and scandalous artists of the day.

This

was where France was 140 years ago... and to some degree it was aided and

inspired by an American. And it was where America was eventually, if

not belatedly headed, almost one hundred years later.

Perhaps

the most famous of all the famous muses was Jane

Burden Morris. Born poor and denied much

education, she was discovered at age 18 by Dante Gabrielle Rossetti

and the “Pre-Raphaelites” in England, and became a popular model

among them.

Like most popular models,

youth was kind to Jane and essential to her exotic beauty. When

Rossetti first saw her, she looked like this. Unfortunately for her,

and art, he did not start painting her regularly for another fourteen

years.

Jane Burden was a quick

study, reinvented herself, and soon carried herself like royalty, as

she acquired ability in music and learned several languages. William

Morris, a major influence in the Arts and Crafts movement, took her

as his wife and she contributed greatly to the success of his

company, especially in textile design. They had two daughters, and

rented a summer home along with the Rossettis for their

entertainment. But when Rossetti's wife and muse passed away, from a

laudanum addiction, and Morris naively traveled to Iceland, Jane and

Gabrielle discovered that they could not resist one another, and a

scandalous affair ensued. Some historians contend that they had been

in love from the very beginning, but Rossetti's marriage prevented

any public attachment.

When Rossetti had buried

his wife he also buried his sexy love poems, written to her, or

someone, which were quite sexually indiscreet. Now he was to turn

exclusively to painting the majestic ideal Arthurian woman with a

vengeance. And Jane became one of his favorite models. He supposedly

painted a woman named Fanny Cornforth as well, but a careful

comparison of her and Jane suggests that most of the paintings, even

ones supposedly of Cornforth, were Jane. Fanny was more of a decoy

for an artsy-craftsy scandal that was just beginning. Jane was the

living, breathing, dark-haired, expressionless siren made famous by

his mysterious canvases.

Back from frozen Iceland,

William Morris, now a partner with Rossetti, and whom he admired as a

sort of mentor, found a sensible and creative solution to Jane's new

obsession. They would all live in one house together. Nobody would

know whose bed Jane was sleeping in. This arrangement did not last as

long as the scandal it inspired. Then after a few years, the

Pre-Raphaelite gang convinced Rossetti that he had buried his poetry

too hastily. His growing fame would make the love sonnets he composed

for his beloved lover a national hit. Everyone could wonder for

generations which woman he was talking about. So she and they were

exhumed. For this crowd, no impulse was denied.

Her beauty somewhat fading, eventually Jane settled

down, charismatic Rossetti succumbed to alcohol and chloral hydrate

(used to treat insomnia!) ... and with Jane's talent and quiet help

William Morris fathered a movement in decorating and architecture

which still commands enthusiasts today...

The captivating features

of Fanny Eaton

Not to be outdone... the

other Pre-Raphaelites had their own muses. Simeon Solomon was the

first to recognize the noble visage of Fanny Eaton, a

statuesque Jamaican immigrant and the wife of a London carriage

driver. Fanny's mother was probably born a slave, and yet her skin

color seems to have been considered part of her charm. She may have

been the first art subject to break the color barrier in

predominantly anglo Europe, being depicted with a certain objective

respect and even admiration for her appearance, regardless of race or

class. Fanny is not believed to have been romantically involved with

any of her admirers, which included Millais and Rossetti, but for a

season she was an exotic distraction from Jane Morris.

As women in France became

“liberated” in the 1870's and were allowed to get educations and

pursue careers, things got really complicated... at least

professional/sexual relationships. Suddenly women were invading a

man's world, stirring indignation and controversy, as former formalities were obsolete,

and minds and a few art careers were blown. Male artists were not

only painting women, nude and otherwise, they were painting alongside

them; Teaching them, organizing exhibits, and competing with them.

Natural elements and human chemistry had to collide as men moved over

and made room. And some like Manet and Renoir moved in...

This of course did not in any way

interfere with the artist-model-muse-lover-wife-mistress complex.

French art had become a censor-free zone of Victorian public nudity,

and artists of all genres rose to the occasion. Gerome painted and

sculpted heroic woman, too strong and magnificent to be clothed,

Chaplin created angelic virgins, uncovered and innocent so as to be

immodest. Degas painted preoccupied ballerinas. Manet edified the

working girl. And his success meant he could afford excellent models;

Victorine Meurent, Meri Laurent, Suzanne Valadon. Monet

painted his wife Camille, prim but faceless. Renoir painted

his pretty young wife Aline Charigot, his children's pretty

young nanny Gabrielle Renard, and his friend's pretty young

daughters, in an avalanche of portly naked womanhood. And all that

restrained testosterone had to go somewhere...

While Cezanne painted

fruit and some really bad nudes, and Pissarro painted trees, most of

the Impressionists and their entourage were interested in painting

people... people living their everyday lives. Courbet had started

the thing... painting outrageously erotic nudes, genre scenes, men

busting rocks on the side of the road, and the idea of real humans in

real-life situations. Suddenly the unemployed and untrained female

had a natural talent for a low-stress, relatively easy job. And as

art became more and more an attraction in French tourism, posing for

an artist was becoming almost the patriotic thing for a woman to do.

Back in the day, poor

young French women had few alternatives. The constant wars and

depressions in France had left the country bankrupt in several ways.

Without educations or status, they had to be open-minded about

marriage prospects. And until they had a husband, they had to be

open-minded about paying gigs... such as modeling for a poor,

not-so-promising artist, just for food. Aline Charigot Renoir

was able to use her beauty to end up on Renoir's canvases, and

eventually in his bed... and to wear his name. It was messy and

tawdry and not to be recommended to anyone. The only problem was that

once she was pregnant and overweight, Renoir would find a new muse...

over and over again, as she gave him three sons. Still, Aline in her

prime was the probably one of the prettiest of the French models of

that day.

Young actress, Henriette Henriot, who

posed for Renoir numerous times, and

may have been his favorite "muse."

Aline was pretty, but

another class of models had arrived on the art scene, that would make

her pale in comparison. It was the wealthy French girl-artist

wanna-be. France was lousy with the type. In fact it attracted them

from all over the world. Wealthy girls had great clothes, and

handsome parents, nice teeth, and well, good genes. They had

educations. Many had art instruction. And as they slyly wormed and

levered their way into the art market, they immediately offered a new

and desirable subject for painting.

Fetching Berthe and

Edma Morisot led the way of this fresh echalon. Edma, an outstanding artist, married Manet's

best friend, and was soon out of the picture, but Berthe held on to

her dream of being a professional artist. She and Edma had studied

under several prominent French artists, such as Puvis Chavannes, and showed considerable

promise when they began to turn heads in Paris. “Too bad they are

women,” Manet had lamented. Being a woman was considered an

insurmountable handicap for even the most talented artist.

Believed by this blogger to be young Berthe Morisot

with her fiance. and sporting an engagement band.

One of

Berthe's first instructors was the sculptor Aime Millet. Soon the

mentor wanted to be the suitor, and they were even engaged. The young

female painter was about to become Millet's studio keeper when she

came to her senses.

When Berthe was wisely

invited into the group of loosely organized “impressionists,”

nobody was sure whether it was because of her talent, or, you know,

the fact that she was drop-dead gorgeous. Ever the opportunist, Manet, who never actually

bonded with the “Impressionists,” did not care, and got her to

model for him often. In fact, no other artist was ever painted so

many times by a fellow artist. And probably no other artist was ever studied and depicted by fellow artists as much as Morisot. Besides Manet and her sister, and herself, and probably her instructors like Millet and Chavannes, she modeled for Desboutin, Bremen and Marcello.

Manet was able to engage her nearly exclusively, within his sphere of influence, but he could not have her. But he could enjoy her company and paint her and have that distinction... although he never did her justice. Meanwhile Berthe went about smoothing over squabbles and keeping the peace among the art beasts of France. Only a classic beauty with brains could have kept them together and actually established a true art movement out of such undisciplined renegades. Like insecure little boys in a tree house, they intentionally met at a bar where she could not go because of French propriety, where they bitched and moaned about her constant interference and ultimatums. But Morisot was one messenger they would not shoot, and she got them to do work together and to establish themselves, for posterity as it turned out. Meanwhile Berthe made brochures and posters, and used her social connections to make headway in spite of them, a reactionary Salon and a hostile French culture.

Manet was able to engage her nearly exclusively, within his sphere of influence, but he could not have her. But he could enjoy her company and paint her and have that distinction... although he never did her justice. Meanwhile Berthe went about smoothing over squabbles and keeping the peace among the art beasts of France. Only a classic beauty with brains could have kept them together and actually established a true art movement out of such undisciplined renegades. Like insecure little boys in a tree house, they intentionally met at a bar where she could not go because of French propriety, where they bitched and moaned about her constant interference and ultimatums. But Morisot was one messenger they would not shoot, and she got them to do work together and to establish themselves, for posterity as it turned out. Meanwhile Berthe made brochures and posters, and used her social connections to make headway in spite of them, a reactionary Salon and a hostile French culture.

Then she got married- to

Manet's brother Eugene, and the Impressionists lost their most

effective public relations agent. She would still paint, but becoming

a mother became a new creative challenge, and one she relished in.

Over the years, Berthe painted her sister, her mother, her nieces and

most often, her daughter Julie, as did insatiable Renoir.

Men paint the objects of

their fascination and fulfillment- and so do women. For men that is

women. For women that is... or used to be, family, and especially children.

Julie

After Berthe Morisot's

death, Renoir was Julie's surrogate father and she his muse. Julie

moved in with Berthe's closest friends, the home of France's popular

poet Stephane Mallarme. His daughters were like sisters to her.

Between the attentions of Morisot and Renoir, the daughter of one and

the muse of the other, Julie Manet replaced her mother as one of the most painted

persons of the French art scene.

Julie Manet (center) poses with two American artists,

Edward Darley Boit and Childe Hassam,

and her close friend, Genevieve Mallarme.

How much Julie posed is a topic for

inquiry. Many of Renoir's nudes sport the round pixie face of Julie

Manet, often attributed to Renoir's children's nanny, Gabrielle, or

Suzanne Valadon, whose bodies were those of more mature, rotund

females, and who made his nudes seem like raucous gatherings of

behemoth libertines. But they often had very small heads, out of

proportion with their bodies, which suggests he used someone else...

perhaps Julie to model for his faces, but not so much exposure of the

rest of her. Renoir was known to use Lise Trehot for his

early nudes, and no doubt recruited Mery Laurent and other models of

the day as well.

Here is a rare, incredible photograph,

which I believe to be the gathering of four of France's most famous

artist's models. This was one of several “grand slams” as I

called them, which I have acquired, impossible groupings never seen

before but certainly possible, of persons from a particular place and

time, whose faces would be hard to confuse with any others. The odds against finding so many "lookalikes" together, from the same period, and the same country, are astronomical. All four of

these women were part of a network of French families involved in the

arts, and in particular the Impressionist school. Lise Trehot on the

far left was Renoir's favorite body model early on. Julie Manet on

the far right was Renoir's favorite head model beginning during her

childhood and for the next twenty years. Above center appears to be

Mery Laurent, who married Stephane Mallarme, a sort of adopted

step- mother to Julie Manet, and a favorite model for Edouard Manet,

Julie's uncle. She was often photographed in Moulin Rouge-styled

dancing garb, and had been a popular entertainer at one time. Mery

once played Venus on the half shell on stage, in the nude, and was

sponsored by a wealthy American in her own salon, where she became

the mistress of France's most admired cultural lights. She

entertained the legends of the times, such as Whistler, Zola and

Proust. Zola based one of his novels on her. The woman on the bottom

may be Gabrielle Renard, Renoir's faithful, convenient, most utilized

model, mistress and baby sitter.

Beautiful Camille

Claudel followed the tragic path of the pretty art student turned

muse- turned lover- turned miserable and shamed. She studied under

Rodin and after an affair was then smothered by his ego and banished.

The other women artists

were not quite so attractive or willingly immortalized; Marcello. Eva

Gonzales. Her sister Jeanne modeled for her. Rosa Bonheur.

Marie Bracquemond. Mary Cassatt, who joined the Impressionists and

took up where Berthe left off. She also painted her sister. And

hundreds of other women. She rarely posed for herself, nor did many others ask her to pose for them. When Degas tried, she hated the results.

Victorine Meurent

was the top model of the day. An accomplished artist and musician as

well, the slender redhead regularly posed for the best artists in

France, including Manet, Degas, Toulouse Lautrec, Puvis de Chavanne

and Alfred Stevens. Victorine was believed to have been romantically

involved with Stevens, but she never married and never had children.

She made her living modeling and painting until, as legend suggests,

her hand was injured. Her art, now almost non-existent, was better

received in her own time, and certainly more than any of the

Impressionists, including Morisot, and she was juried in to the

annual Salon exhibit in 1876, her self-portrait beating Manet as she

was accepted and he was not. Only three or four of her paintings have

been preserved, including the self-portrait which established her

talent and made her the most essential and most adored woman in

French art history.

It is Victorine who is

believed to have modeled nude for Manet's scandalous blockbusters,

Dejeuner Sur de L'Herbe (The Bath) and Olympia. She was also supposed

to have been the boy in Manet's The Fifer. It has never seemed to

bother art historians that these people did not look like one another

and did not look like Victorine. But history said so. French art

history was written long ago, and that was the end of it. As a blogger, I have the freedom to challenge some of these long held assumptions and offer a twist far

more interesting.

First of all, when you imagine Victorine,

think Nicole Kidman. Then as you scrutinize

Manet's final version of Olympia, hold that

thought. You can have only one conclusion:

No way!

Victorine grew up in a

blue collar family. Both of her parents were industrious and even

creative. Her mother was a hat maker, her father a craftsman at a

foundry, and she was a budding artist. She started modeling for Thomas Couture in 1860, when just

sixteen years old. That is where she may have met one of Couture's students, Edouard Manet, who would later draw her into the greatest controversy of her life.

Somehow this girl from humble beginnings learned respectable skills in music and painting, and had the good looks to make money by just sitting still. Manet supposedly hired Victorine to model for a battery of projects, including The Street Singer, Mademoiselle V and The Bath around 1862, meaning this very beautiful girl from self-respecting origins, with artistic skills of her own, agreed to pose as herself, a bull fighter, and nude in the role of a courtesan for a virtually unknown artist. And she was only eighteen.

Somehow this girl from humble beginnings learned respectable skills in music and painting, and had the good looks to make money by just sitting still. Manet supposedly hired Victorine to model for a battery of projects, including The Street Singer, Mademoiselle V and The Bath around 1862, meaning this very beautiful girl from self-respecting origins, with artistic skills of her own, agreed to pose as herself, a bull fighter, and nude in the role of a courtesan for a virtually unknown artist. And she was only eighteen.

All of this is possible,

but at eighteen auburn-haired Victorine was lithe and sexy, unlike

most of the females Manet was to portray. She may have posed for The Singer, hiding her face, and some for Mademoiselle V, even though the

likeness is minimal, but the portly gal in The Bath is quite solid,

with enormous thighs, and brunette. A smaller exploratory version, which sports a

redhead, looks as if Manet may have stuck Victorine's head on a very

large-bottomed woman. This suggests that Manet used Victorine, not surprisingly, mostly as a head model. Early photographs of Victorine Meurent suggest

that she was lean and well proportioned, and classically long faced.

The somewhat hefty, but sexy woman in The Bath looks to be far older

than eighteen, and shamelessly flattered by any attentions, honorable or otherwise.

Manet came out the next

year with his most famous work, Olympia: a bold prostitute spread out, looking the viewer

square in the eye, with nothing covering her nakedness but her sporty house shoes. The woman is obviously short and stout, and round

faced- a Mediterranean brunette, and actually looks a great deal like

Suzanne Valadon, but who was only three years old at the time. Art critics

have opined about the scandal of Manet painting Victorine, a nineteen-year old

art student in such an outrageous context. And how many people, as has been supposed, would

have recognized his model, and been all the more

excited or offended. Really? They never saw the earlier sketches... and Olympia had nothing in common with Victorine except that both were female. But Victorine had probably bragged that she had been modeling for the artist... and people did the math.

Yes reader, the story behind the painting has always been as important as the art.

Yes reader, the story behind the painting has always been as important as the art.

Victorine Meurent has been recorded

by history to have posed for as many as nine of Manet's masterpieces,

over a twenty year period. And there were probably more. But five of

them were modeled before the end of 1863. Two more were modeled in

1866. Then there was a seven year lapse. It was during this time that

Victorine really honed her own painting skills, and posed regularly

for Alfred Stevens. Stevens' tasteful, precise style of art was more

to her liking than the crude swaths and risque subjects of Manet's

canvases. The last time she posed for Manet was in 1873 when

Victorine sat, still elegant and gorgeous, for The Railway,

completely clothed with a child at her side and a puppy in her lap.

It is important to note that she was rarely known to pose in the nude

for artists. When she did, she never the less covered herself

prudishly. Stevens once supposedly managed to expose one breast, but I think that painting has been mis-attributed. The model for that was probably Mery Laurent, someone far more likely to throw caution to the wind. And after

Olympia, no one was to ever see Victorine's naked waist or legs, or even her

feet again.

This is one reason that I

am suspicious of the use of Victorine as the primary model for any nudes at all. But yes,

I think artists used her face in a number of ways. Artists are

ruthless composers, in search of the elements of their inner visions.

They are body snatchers... body part snatchers... gesture and

expression snatchers... always on the hunt for a sly grin or the

gleam of the eye... a nicely defined muscle. The idea that they would do this seems to be lost

upon non-artists, who think in a linear way. A picture of a woman

must be a picture of someone- a presentation of a person in a

time and place- a sample of that moment, and an expression of...

truth.

But to an artist, a picture of a woman might be the culmination of everything he or she has ever learned, or loved or experienced... and often the conflation of a lifetime of observations and preferences and... the artist's ideal. In other words, a larger, all-encompassing truth.

But to an artist, a picture of a woman might be the culmination of everything he or she has ever learned, or loved or experienced... and often the conflation of a lifetime of observations and preferences and... the artist's ideal. In other words, a larger, all-encompassing truth.

Olympia was such a

composition. Every painting is. Who modeled for it? Maybe Victorine, at least for the thumbnails and preparatory studies. Or maybe an unknown prostitute. Or both. The earlier sketches of the

composition feature a slim redhead... but she quickly disappears. In the end a very different type emerges on the final work. Or

maybe Manet was dreaming the whole time about his wildest fantasy, or

his mother, or maybe someone whom will never be told, buried

underneath all of the stupid speculations and assumptions. But sadly,

for people to get interested in art, there must be a story,

preferably naughty, behind it.

It was such fun for the

French, enjoying their sexual revolution, to imagine that the model

for Olympia was the sexy teen-aged redhead. And Manet was glad to a

point- for morons to make up stories and fuel the fires of

controversy. As one of my artist friends once discovered, and

explained pragmatically after being labeled in a negative way in the

Austin newspaper, “It does not matter what people are reading about

you, as long as they are talking about you.” For artists, scandal

is the equivalent of free publicity. My friend reasoned that a year

later they won't remember what they read or heard, only that you are "famous."

It was said that after the

wild, unexpectedly hostile public reaction to Olympia, Manet was

mortified and fled the country. He could not have been that

surprised, nor the French so outraged, and surely the French had seen

a nude before, many of them. What was the big deal? Manet was merely

following a natural progression, after being inspired by the works of

Spanish masters such as Velasquez and Goya. In fact his paintings

were direct answers to their greatest works. Still, there was wailing

and gnashing of teeth. And surely they were not so upset about the artist's choice of footwear...

A brazen nude, staring at the onlooker,

had been done 300 years before, and

many times since... but always BAREFOOTED.

Why the fuss?

Why the fuss?

It boiled down to Manet's

attitude. He was not liked, and art critics were determined to be

less than charitable. His courageous canvases were attacked as much

for political purposes as any real concerns about art. As with any

controversy, the facts pertaining to the painting were thrown around

loosely to sell newspapers and... well, contribute to the fun. A

casual nude woman, simply resting as a servant presents a fabulous

spray of flowers... which I'm told would have been no big deal to

Europeans... presumably an honest depiction of a "working girl," who suddenly transformed into a brazen whore, unashamedly looking at

her onlookers, and an unacceptable breech of social interaction.

Naked ladies were not supposed to look at you. That was the advantage

of art: You were supposed to be able to goggle at a naked woman, and

not feel any discomfort. And in truth, it had been done before... by

Goya and others.

One of Manet's associates, the ill-fated young French

master Bazille painted a similar painting just before the

Franco-Prussian debacle, when he was killed in action, his answer to Manet's answer to Goya's answer to Titian's... We will never know, but he seemed to be trying to meet with the critic's approval, as his nude's waist is covered, and she wears only one turquoise shoe...

Chaplin's maidens were a little more shy, rarely looking towards their admirers when bare-chested. Clement and Courbet had already been cranking out brazen, buxom, naked ladies for several years. Certainly Parisian art enthusiasts were not looking upon anything they had not seen before. The objections today seem shallow and infantile. But just as today, it was not so much what Manet said... but how he said it.

La Toilette, by Frederic Bazille. 1869-70.

Bazille's alabaster, long-limbed beauty

looks more like an Olympic swimming champion...

resting after a round in the boxing ring!

Chaplin's maidens were a little more shy, rarely looking towards their admirers when bare-chested. Clement and Courbet had already been cranking out brazen, buxom, naked ladies for several years. Certainly Parisian art enthusiasts were not looking upon anything they had not seen before. The objections today seem shallow and infantile. But just as today, it was not so much what Manet said... but how he said it.

How Victorine might have

felt, we can guess by her choices from those days forward. She

modeled for Manet much less... finally breaking away and modeling

only for artists whom she could trust to protect her dignity. But at

the time, and ever since, she has been pigeon-holed as Manet's muse.

Wild speculations continue even today, as nude souvenir photographs

of a fully mature woman are brandished on the Internet as her, even

though she would have to have been only thirteen years old when they

were made. The art world wants its muses dark and nasty. Scandal has always been the selling point of art. Later European galleries would perfect this strategy marketing Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. Lunacy, self-mutilation and debauchery in exotic places superseded the mild glimpses of the world's oldest profession. But in the early days, artists fully expected to rise through artistic excellence and the recognition of it. If Manet left the country in humiliation, we can only imagine what

anguish and depression might have followed young Victorine, equated at twenty with the whore of Babylon.

In 1866 Manet released his

Le Fifre, an adorable portrait of a young military musician... which

was supposedly based, again on Victorine. At twenty-two years, it is

safe to assume that she looked nothing like the young boy in the

painting. Not the height, nor the face, or the sex... That art

historians have accepted and believed and taught these

identifications for so long just proves how little most art critics and "experts" really

know about art or artists or human beings. I don't care who

originally made these claims. They were either ill-informed or lying.

It seems that Victorine

Meurent became a catch-all for any mysteries in Manet's sources.

Someone in a moldy French gallery basement was trying to catalog his works and just made a stab at Manet's probable

models, and wrote it down, and Meurent was certainly a probable, and then somebody else repeated it... In fact they both probably

wanted to think that the paintings had been modeled by Victorine. It

was sexy to think of the beautiful redhead beneath the fifer's

uniform. And more importantly, it would help sell the most mundane of

portraits. I can hear the art dealer telling his sales staff,

“...Tell them it was Victorine... the Americans will snatch it up

immediately!”

The impossibly contradictory faces of

Victorine Meurent. The alleged nudes...

Victorine Meurent. The alleged nudes...

The green background on the Rt encompasses

those captured by Alfred Stevens... and perhaps

those captured by Alfred Stevens... and perhaps

the most accurate. Bottom left and center are Manet's round-faced subject, long considered to be Victorine.

Let's compare! What could be the reason for all of the inconsistencies? How could two artists see one woman so differently? I will strive here to put all of the confusion to rest.

First, let's look at this

lady, The one in Manet's paintings... and study how a better portrait painter depicted Victorine, a veritable Victorian template for Nicole Kidman- and how he

actually captured her face. Alfred Stevens saw an entirely different

person than Manet often did, and certainly one more consistently

beautiful. Victorine did burn off some “baby fat” in the early

years, and then added on some weight as she aged, but she was never

short, or pear-shaped, never full-lipped, never a changeling whose

skull stretched or condensed as Manet's “Victorines” seemed to

do.

The metamorphosis of Olympia along

the bottom... from redhead to brunette.

The weathered face of Suzanne Valadon's

mother, upper left. The various versions

of Suzanne by several artists, top row.

Morisot and Renoir got it right, showing

Valadon's oval face.

My observation about the similarity of Manet's Olympia to Maria “Suzanne” Valadon, a popular model, and mistress of Lautrec and Renoir, and an accomplished artist in her own right, has brought me to my own, not so baseless speculations. Born out of wedlock and never knowing who her father was, she was too young to have been a part of the creation of Manet's groundbreaking works. But her mother would have been, not only similar in looks and stature, but the perfect age to have been a model and lover of Manet's. And the striking similarity of Olympia to Valadon cannot be ignored.

An older picture of Susanne Valadon (Rt) compared to

a portrait she did of her mother in her old age,

show several facial similarities, including wide

cheek bones, arched eyebrows, an upside-down smile

and a downward sloping nose. Might her mother looked

as much like her daughter in her youth?

“Suzanne” Valadon was given her nickname by

Toulouse Lautrec; a biblical reference recalling an innocent young woman

hounded and blackmailed by would-be older lovers.

Another clue was Manet's "coincidental" depiction of the Susanna story in Dejeuner Sur de

L'Herbe, better known to the English speaking world as Luncheon on the Grass, Manet's modern reenactment of the

negotiations between two interested men and a young woman, supposedly

having just bathed. The Susanna in the painting is listening to their

overtures and looking at us, as if to say, “Here we go again!”

A preliminary sketch of Dejourner does feature

a redhead... her head very small in proportion to

the rest of her body. But look at those massive arms!

And that gut! The body of a mature woman.

When we admit that the full, round face in the larger version of this composition barely resembles Victorine Meurent, and her muscular body in no way suggests the youth or slender attractiveness of the famous model, we can at least toy with the idea that someone else modeled for the final painting.

Manet's theme not only perfectly parallels the Susanna legend, it may have been an unwitting clue, when Lautrec's conflation is added to the soup. Lautrec saw in Manet's painting the perfect illustration of a Bible story, the parallel of which he knew his lover was caught up in. She became "Suzanne," the French cognate for the ancient name Susannah. The significance of this religious legend should not be overlooked.

Lautrec, a struggling artist who loved Maria and knew her “intimately,” may have given her the name “Suzanne” for deeper reasons than the mere ogling of her grizzled old mentors and employers, artists like Renoir and Chavannes, as has often been repeated. In the apocryphal story of Susanna and the Elders, two lustful and powerful men conspire not only to have their way with a beautiful woman while she bathes, but threaten her if she tells anyone of their advances. They try to blackmail her, saying they would use their considerable influence to have her arrested and stoned for adultery, and they were willing to bear false witness against her to do so. In other words, “Submit or we will make your life miserable.”

But Susanna is strong and

does not yield to them. And her reaction not only drew attention to

the situation, but it put her in deadly jeopardy. She argued with the

blackmailers...

Suzanne

Valadon was

quite pretty and often modeled for Chavannes,

Manet and especially Renoir- and is believed to have bedded with some

or all of them... There is no doubt that she was embraced, groomed

and nurtured to become the first French woman accepted into the

prestigious Société

Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Yet, things were political then as they are today, and I believe she was also being compensated by the art community- for past

injustices.

The missing piece, a long

neglected person in this drama who brings my theory home, if it has a home, would have been Madeleine Valadon, Suzanne's mother, the possible target of the blackmail, who arguably could have looked a great deal like Suzanne when

she was young. And a generation before was a single woman trying to make

a living in hard times... perhaps yielding to offers to pay her to

model in the nude... and horror of horrors, when Olympia created such a stink, then worrying about her

family and friends learning of her leanings towards what many Frenchmen considered prostitution; And then living with that threat all of her life.

And her unwillingness to be exposed kept her from getting fair treatment from her artist/employer/lover... who possibly fathered her child... and never helped to support her... and the mother chose to raise the child without help, and if the artist was Manet, rather than take the risk of being embarrassed as a model and muse who inspired a national scandal.

What if one of these artists, so quick to nurture and edify Suzanne, was actually Suzanne's father, making things right with her? And all of this circle of artists knew it, and eventually all of them later adopted her into their “family,” and collectively oversaw her artistic success? She was accepted in time into the status of recognized artist, and Degas assured her that “You are one of us,” after purchasing one of her early works. Perhaps she was one of them more than they would ever admit.

And her unwillingness to be exposed kept her from getting fair treatment from her artist/employer/lover... who possibly fathered her child... and never helped to support her... and the mother chose to raise the child without help, and if the artist was Manet, rather than take the risk of being embarrassed as a model and muse who inspired a national scandal.

What if one of these artists, so quick to nurture and edify Suzanne, was actually Suzanne's father, making things right with her? And all of this circle of artists knew it, and eventually all of them later adopted her into their “family,” and collectively oversaw her artistic success? She was accepted in time into the status of recognized artist, and Degas assured her that “You are one of us,” after purchasing one of her early works. Perhaps she was one of them more than they would ever admit.

And since she played nice,

they did as well, and the blackmail held over her mother was ended,

and she found her “family.” And then a young painter of

prostitutes (Lautrec) lived with her and dubbed her "Suzanne," reflecting the dark, complicated world in which she had endured and

prevailed.

Surely no other artist or model in France better embodied Olympia, and no other spent such a great deal of their life identifying with the painting. Suzanne seemed to say with many of her own nudes, often reminiscent of Olympia, “I know who Olympia is!” She was proud of her associations, and yet (I suggest) bound to never tell... to protect all parties involved. And Victorine had already been taking the heat for twenty years. It was old news.

Surely no other artist or model in France better embodied Olympia, and no other spent such a great deal of their life identifying with the painting. Suzanne seemed to say with many of her own nudes, often reminiscent of Olympia, “I know who Olympia is!” She was proud of her associations, and yet (I suggest) bound to never tell... to protect all parties involved. And Victorine had already been taking the heat for twenty years. It was old news.

Since Valadon admitted

that either Chavannes or Renoir were the father of her son, because

of social taboos on incest we can reduce the suspects of who was her

father. Then Manet emerges again to the forefront. The man who

painted the mysterious Olympia, who refused to ever publicly support

the Impressionists for fear of their negative association, or clear Victorine

Meurent of her undeserved social discomfort, the greedy artist who

always elbowed his way to the front to paint the most beautiful

French women, but who rarely did them justice. Did Manet paint

Dejeuner Sur de L'Herbe as a cunning warning of blackmail of an heretofore

unknown model, and mother of his unclaimed child, releasing his

masterpiece as a blockbuster and simultaneously as a looming threat to the modern day Susannah?

We will never know. But it went down something just like this.

We will never know. But it went down something just like this.

So mercifully, for noble

reasons, or perhaps not so noble, my theory proposes that Suzanne's

mother was cheated out of the fame in history for starring in the

most scandalous nude in France in her time. Or dodged a huge bullet... But she lived with a real

fear of wearing the public shame heaped on Victorine Meurent, if the

artist of Olympia ever set the record straight. Manet craved the

attention, the reputation, the glory. He would share with no one.

All while he took his long-suffering wife for granted (yes, he had a

common law wife- ironically also named Suzanne) and seized every

opportunity and slithered out of every encumbrance.

Ruthless, ambitious,

relishing in attention even if it was negative, it is easy to imagine

Manet as the blackmailer of Lautrec's Susannah; The manipulative

artist who got a poor model to give up her modesty or much more; the

wanna-be master held back by his poverty... and poverty of mind-

perhaps unable or unwilling to pay his first hapless models, or marry

those he impregnated, as he skirted responsibility... as he did in

every facet of his life. But in my imagined Lautrec scenario,

Susannah was the daughter of the wronged woman, bravely facing the

elders, and being lavishly compensated for her mother's lifelong

oppression.

My proposed scenario

answers several long standing curiosities. It explains why young

Victorine Meurent was falsely saddled with a ludicrous rumor, the

chosen fallen woman, and while young Suzanne Valadon was escorted to

the height of French art achievement, her fallings were kept discreet. Why

the most prominent of the Impressionists embraced her, helped her,

taught her, and yes bedded her like “one of their own.” Why

sexuality, not family or children, was at the core of Valadon's art;

Why Suzanne spent most of her art career painting nudes, many with

the very same “in your eye” expression as Manet's masterpiece.

Why many of her paintings were of herself, at least nude to the waste, seen

from a mirror, looking at the world with a sneer, in the very spirit

of Olympia.

Without women, Manet's

portfolio would have been a few bad self-portraits and some luckless

elders sitting in the woods looking at one another. Suzanne was not

just a great model and artist, she may well have been “Olympia's”

revenge... and atonement. Long overdue acknowledgment- payment for

services long since rendered. Such a paradox, if so.

Because

it was Manet who breathed excitement into the French art

scene, even when the judges refused to reward him. Manet who made

women of common origins the focus of society. It was Manet who

discovered and edified Morisot and Meurent, and introduced French

beauties such as Guillemet, and Demarcy. It is obvious that they were

his obsession. That he thought about nothing but women. That women

were his reason for painting if not for living. Yet he will always be

remembered as the exploiter, the user, the man too busy achieving to

be bothered with love or sentimentality. Women were the ultimate in

Creation. But women were also the earth under his feet... perhaps the

dirt between his toes.

So Manet, make up your

mind. Like Rembrandt and most artists since, Edouard Manet was a man

before he was an artist, and he thought and acted like the worst of

them, even while he worshiped the muses he exploited. The passion and

human contradictions have fascinated art lovers for generations.

In spite of his flaws,

Manet in many ways was the instigator of the Western vision of

women's liberation. His bathers, and especially Olympia, who became

the symbol of female charms, both wholesome and illicit, in a

controversial epiphany, were awarded a strange kind of dignity in

their brazen exposure. Olympia insolently stared back at a world

which had always condemned or denied her, and took the bouquet, and

whatever else due her, making sex a normal function, rather than the

habits of animal instincts. And Suzanne Valadon became the living

embodiment of his allegory.

The servant, the flowers, the luxurious bedding, she had earned them. Olympia had taken her place as not only the muse of a blunt painter, but of all humanity. The muse, the giver and keeper of love, the confessed obsession of art and literature and music, of most of mankind... and of most entertainment and advertising today... Olympia became the true, irrefutable goddess of mankind, just as Queen Victoria began her thorough campaign to establish otherwise.

The servant, the flowers, the luxurious bedding, she had earned them. Olympia had taken her place as not only the muse of a blunt painter, but of all humanity. The muse, the giver and keeper of love, the confessed obsession of art and literature and music, of most of mankind... and of most entertainment and advertising today... Olympia became the true, irrefutable goddess of mankind, just as Queen Victoria began her thorough campaign to establish otherwise.

Queen Victoria threw all

the influence of her empire at her impossible task, to make woman

submit to her vision of civilization, to hypnotize the Western world

into the subversion of sex, the forbidding of the very words used to

discuss it. And still Olympia glared back, until she eventually won.

Another epic example of the power of art.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for sticking your finger into the fire...please drop your thoughts into it!