Many

red-blooded Americans will naturally wonder, what did France

have that we did not have?

Most importantly, France was one hundred years ahead in its own social evolution. By the 1870's, France had established a strong merchant class, who had suffered and struggled through wars and upheavals and was ready to let the good times roll. Unlike England or Germany or the United States, it had no strong Protestant population to object. Furthermore, England's Queen Victoria (left -handed) and the disciplined, prudish "Victorian era" inspired by her was a hard sell in France. The British were very Protestant and conservative, the French were traditionally Roman Catholic and liberal.

France had already established itself as an art and fashion center, parallel with any in Italy, and it had thousands of art enthusiasts. Many philosophers and writers and artistic types were drawn there and permeated its society much like in Hollywood today. Napoleon III had nurtured the Arts like none before, even providing a venue for the artists juried out, those summarily refused at the annual government sponsored art exhibit. Even that show drew thousands, where the avant-garde met the clueless. If the art wasn't just downright awful, it was intentionally controversial and insulting. The controversy stimulated by that mismatch only attracted more American fans, who loved the idea of underdogs being bad, and taking on the establishment.

If Courbet was a sort of benign uncle to the Impressionist family, and Pissarro a soft-spoken father, then Claude Monet became the big brother. He was stable, fair minded and a damn good artist. But most of his remarkable positive attributes only surfaced after the first severe tragedy within the Impressionist family. And it was a monster.

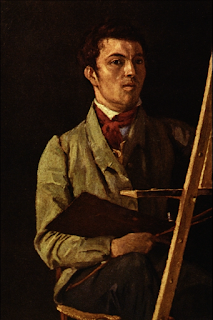

Self-portrait of Claude Monet

The artists reacted much like the population. They were split between the patriots who chose to defend their country (and the status quo), a few who sought refuge during the firestorm, and Courbet, who got caught up in the excitement, and joined the “Communards.”

L@L Frederic Bazille

Monet's close friend, fellow artist and sometimes financier Frederic Bazille was killed in the war. Bazille was from a wealthy family and always managed to provide for the two of them, even after Claude was married and had a child to provide for. It was Bazille who doctored Monet when he was nearly crippled in a freak accident while painting plein air. A true innovator, like a professional doctor he put Claude's leg into suspension and then painted him while lying helpless in the contraption.That is right-brained behavior.

Bazille was tall, strong, humble, diligent, and faithful. He was immensely talented, and his style of painting helped set the direction of the new art movement. Most of all, being a lefty, Frederic was what Monet was not, a problem solver. So Frederic Bazille was the very best friend and art companion Monet could ever have. But Monet was unhealthily dependent on Bazille, and unmercifully siphoned off of his generosity. When in trouble with his finances, unable to pay his rent or feed his family, he would lay an unreasonable guilt trip on Bazille, who always came to the rescue. Unlike most of his narcissistic associates, Bazille always answered the call to duty to friends or his country.

When Monet's artistic soul-mate was killed while leading his fellow warriors in a retreat down a muddy road, the untimely death ended Monet's extended childhood. He seems to have absorbed some of Bazille's sterling qualities, and he morphed towards the man he needed to be.

War also brought out the "survivors of the fittest." After being recruited into the French cavalry, Renoir admitted that he had never actually ridden a horse. Being in the cavalry was usually reserved for men with social standing and connections, but certainly riding ability. But when his cavalry captain learned he was an artist, he ended up teaching art lessons to the captain's daughter. This was the story of his life. Renoir supposedly eventually learned to ride, and to train horses.

He claimed the secret was to treat the horses just like he treated his models; let them do whatever they want, and pretty soon they will do whatever you want. Ever the cynic, he saw no glory in Bazille's sacrifice, to him his death was a symbol of the futility of the war.

Most importantly, France was one hundred years ahead in its own social evolution. By the 1870's, France had established a strong merchant class, who had suffered and struggled through wars and upheavals and was ready to let the good times roll. Unlike England or Germany or the United States, it had no strong Protestant population to object. Furthermore, England's Queen Victoria (left -handed) and the disciplined, prudish "Victorian era" inspired by her was a hard sell in France. The British were very Protestant and conservative, the French were traditionally Roman Catholic and liberal.

France had already established itself as an art and fashion center, parallel with any in Italy, and it had thousands of art enthusiasts. Many philosophers and writers and artistic types were drawn there and permeated its society much like in Hollywood today. Napoleon III had nurtured the Arts like none before, even providing a venue for the artists juried out, those summarily refused at the annual government sponsored art exhibit. Even that show drew thousands, where the avant-garde met the clueless. If the art wasn't just downright awful, it was intentionally controversial and insulting. The controversy stimulated by that mismatch only attracted more American fans, who loved the idea of underdogs being bad, and taking on the establishment.

Le Moulin de la Galette by Renoir

Soon

a new industry was born, selling “bad art” to the adventurous, especially open-minded

American collectors. Galleries sprung up, and careers were launched. The

new trouble-making artists, free spirits called “impressionists,” were mostly

well-educated sons of privilege, young artists with mediocre

skills, living off of their family money, often spurning jobs at the

family bank or mercantile.

Conventional lifestyle was an anathema to them. Menial work did not appeal to them. Traditional art did not appeal to them. They spurned academic art education as if it were a dead-end road. The “Impressionists” accepted the whole Bohemian philosophy without hesitation, and mostly because they could. This means they were much like gypsies, where the term came from. They lived somewhat poor, following their passions, moving as necessary to avoid responsibilities like paying bills or meeting other obligations. My generation called them hippies. They were contented to be together and live a hand-to-mouth existence, and never worried about having employment, or how to get money. They lived off of each other or their parent's subsidies, so the artists did not necessarily have to sell their wares to survive. They were, from our perspective today, the first “Millennials.”

Conventional lifestyle was an anathema to them. Menial work did not appeal to them. Traditional art did not appeal to them. They spurned academic art education as if it were a dead-end road. The “Impressionists” accepted the whole Bohemian philosophy without hesitation, and mostly because they could. This means they were much like gypsies, where the term came from. They lived somewhat poor, following their passions, moving as necessary to avoid responsibilities like paying bills or meeting other obligations. My generation called them hippies. They were contented to be together and live a hand-to-mouth existence, and never worried about having employment, or how to get money. They lived off of each other or their parent's subsidies, so the artists did not necessarily have to sell their wares to survive. They were, from our perspective today, the first “Millennials.”

Edouard Manet created and exhibited "Olympia" for one reason, to shock and dismay. For the first time in art history, an arrogant prostitute was depicted totally naked, looking shamelessly into the eyes of the viewer.

This race of

super-Frenchmen lived passionately, loved and traded-off freely, and

often avoided marriage, regardless of fathering children. It was far

more important to serve the vision, the mission, and above all else,

maintain the monthly stipend from indulgent parents, long since

ambivalent about their belated maturity or success. Some upper-class

French families still made appearances about such things as

propriety, and just quietly expelled their delinquent grown children, salving their guilt by throwing money at them and quickly looking the other way. But

the artists' fans were mesmerized. If the art was lacking, the story behind

it was a new adventure everyone could participate in.

The

French Impressionists were like a huge co-dependent family

network in a relatively small place. Sure that small place was Paris,

and it was an art haven, but the social climate and patent public

rejection drove the determined artists into a instinctive support group. They had one

ace to play, and that was the influx of American money into an

otherwise mediocre art marketing scheme, and that helped to push the

movement over the top. Meanwhile the French establishment made fun of the new art

and more or less boycotted it.

The artists were painting

portraits, cartoons, murals, anything to stay alive. They painted

their wives, their children, the food on their table, prostitutes and

vagabonds. But they encouraged one another, in a special way that

persecuted people will. One writer has attributed their common bond

to be sheer determination. That fits in to my use of the earlier

quotation about persistence attributed to Calvin Coolidge.

Determination for sure, but something far less noble lied beneath.

Self-portrait by Claude Monet

These Impressionists were a willful tribe

of malcontents, non-conformists, freeloaders, dreamers and users. In

almost every case, they had no one else, no place else to run and

still maintain their autonomy. They were living in hovels, racking up

spiraling debts, running from reality and responsibility.

The Impressionist movement was born out of rebellion and the intolerance and idealism of youth.

The Impressionist movement was born out of rebellion and the intolerance and idealism of youth.

They fanned each other's

flames. They behaved very much like a commune or a fraternity, but

with more determination. Pride had a lot to do with it, nobody wants

to give up on their delusion and go get a job... and nobody wants to

deliberately do anything to satisfy their parents! And yet there was

something altruistic binding them as well. They were doing something

important for art, they were agents of change. The more they were

maligned, the more they nurtured one another. They understood one

another. Or in some cases like Cezanne, they indulged or tolerated one another.

Impressionism did not just

erupt one day in Renoir's figure drawing class. Older artists like

Corot and Courbet and Pissarro had been snubbing convention and

painting out of doors and portraying “ignoble” or “unsuitable”

or even "indecent" subjects for decades. Check out some of Rembrandt's etchings.

Tight realism had been yielding since the Romanticists had emerged, and the so-called Barbizon Realists were often loose with the brush. Velasquez of Spain preceded them and was loved and studied by most of them, and could out-paint any of them on that score. What was so unusual about the new art was the abandonment of “worthy” subject matter, the intentional use of the mundane, even the vulgar and grotesque. But these kinds of subjects fit unpretentious American sensitivities quite well.

Like many renegades, Corot was a lefty...

Tight realism had been yielding since the Romanticists had emerged, and the so-called Barbizon Realists were often loose with the brush. Velasquez of Spain preceded them and was loved and studied by most of them, and could out-paint any of them on that score. What was so unusual about the new art was the abandonment of “worthy” subject matter, the intentional use of the mundane, even the vulgar and grotesque. But these kinds of subjects fit unpretentious American sensitivities quite well.

Even

American art students were rebelling. Their instructors were

the finest in the academic art world, many of them trained in the

“Old World.” Whistler had been to England and France, absorbing

as much wisdom as he could between affairs and social engagements, from Courbet,

and Baudelaire and others, who had not yet made the stylistic break

with conventional methods, but understood the importance of breaking

away from traditional subjects.

L@L Mary Cassatt with her painting teacher,

the renowned Jean Leon Gerome.

Mary Cassatt was fortunate

enough to be allowed to enroll in classes under the esteemed Jean

Leon Gerome. She was American, and a female, and her opportunity was

seldom extended to any young talent like hers. But hers was exceptional, "even for a female." Unlike the United States, liberal French society was beginning to open up to women in roles besides homemaking or cooking. Still Gerome's expertise and powerful paradigm

faded out like a cheap dye on the first rinse.

Cassatt befriended the

young, bohemian set in the Paris cafes, and with an invitation from Edgar Degas, she joined the Impressionist family. Gerome retaliated by persecuting the impressionists who dared to enter the

government sponsored art exhibits, where he was a prestigious juror.

Cassatt seems to have been a favorite of Olivia Clemens's, or someone in the

family, because there are tintypes of her in every stage of her life,

following her from her posing with Gerome to middle age. There are

even photos of her mother, who sometimes posed for her.

Mrs. Robert Simpson Cassatt, by Mary Cassatt

L@L Katherine Kelso Cassatt,

Mary's mother around 1890

Mary's mother around 1890

If Courbet was a sort of benign uncle to the Impressionist family, and Pissarro a soft-spoken father, then Claude Monet became the big brother. He was stable, fair minded and a damn good artist. But most of his remarkable positive attributes only surfaced after the first severe tragedy within the Impressionist family. And it was a monster.

Self-portrait of Claude Monet

L@L Claude Monet (1840-1926)

As has often been the case, the Prussians

sensed a weakness in the French that was irresistible to their need

to organize and dominate. France was stirring with “republican”

revolutionaries (led by Courbet!) who would surely lead to a messy civil war. Prussia (Germany)

would no doubt have to get involved, so why not just take it and fix

it... and own it... and have wonderful ports and the prestige of

Paris... Hence the Franco-Prussian War.

Even as the over-confident Prussians moved in and surrounded

Paris, the “republican” element began to organize. Labor unions,

anti-monarchists, anarchists, artists and plenty of rootless

troublemakers coalesced into a formidable underground. The French

government would have to fight on two fronts.

The artists reacted much like the population. They were split between the patriots who chose to defend their country (and the status quo), a few who sought refuge during the firestorm, and Courbet, who got caught up in the excitement, and joined the “Communards.”

Monet and Pissarro fled to England,

where Durand-Ruel was setting up a new gallery, successfully

marketing his mountain of French art. As usual, Monet was just

following his usual path of least resistance, and just being

self-serving. But Pissarro found consolation in his flight in that,

as his mother insisted, he was not actually French. It was not his fight. Berthe Morisot

found refuge in small out of the way villages, making excuses why she

still could not paint. The truth was that together they were an

exciting movement, but individually they were merely unmotivated, depressed young

people.

Conversely, Renoir and Bazille joined

the French Cavalry. Degas and Manet were more reserved, enlisting in

the National Guard... where Berthe Morisot, ever sarcastic, chided

that Manet spent the war changing his uniform. War always brings out

the extremes... even the positive facets of personalities. For a

brief moment, we saw Degas join something bigger than himself, and the

flirtatious Manet learn to miss and adore his absent lover, whose

photograph he learned to find great comfort in. During the siege of

Paris all of them were deprived of proper nutrition and lost the fat

of youth, slimmed down, becoming lean and wiry. Too old to fight,

Courbet tried to assume the role of statesman. He considered himself

to be part of the brain trust of the Communards, who grew in power

daily.

When the war went badly, the

Communards, calling themselves the Revolutionary Socialist Party,

blamed the government, and decided it was time to revolt and take the

power back to the people. They blamed Napoleon III for “the ruin, the

invasion and the dismemberment of France.” Courbet even entered an

election to be a representative of the new revolutionary government.

Civil war was unavoidable, and was in full bloom by 1871.

After surviving the siege, and now

finally afraid, 700,000 citizens fled their beloved city of Paris.

After a bad whipping from the Prussians, the authorities were in no

mood for mercy. In the end, the hardships of the war taught many

lessons, and they were purchased with blood. Pissarro learned that he

could run and hide, but he could not save his home, which included a

large inventory of unsold works. With no one to protect his

interests, the Prussian army used his house as a stable and latrine,

and his landscapes were cut from their frames and appropriated as

groundcloths and aprons in a makeshift butcher shop. His home and studio

destroyed, peasant women salvaged the remaining canvases and used

them for handy “oilcloth” aprons. So much for the French love and

appreciation of art.

20,000 Communards were killed in the

conflict, and 40,000 were eventually captured by the Federal forces

as the French began to regain order. Many were tried and executed.

Gustave Courbet was allowed to live but was court-martialed and exiled.

After serving in the French cavalry as a horse trainer, Renoir was almost summarily executed for suspicious activity. Returning to his comforting habit of plein air painting after the conflict, someone decided that he was using his easel as a cover for a spy operation. The young war veteran and Impressionist painter was taken into custody.

He spotted an officer whom he had once saved from a similar situation, now in power to save his life. Ironically, he had once allowed the young man his extra easel to impersonate as an artist when authorities were trying to round him up, and the disguise had worked. Now being marched to the firing wall, the officer could return the favor. He snatched Renoir from the jaws of certain death and obscurity. No turn goes unpunished they say, and the gallant officer was murdered soon after. With all this deadly intrigue, it is a wonder that “plein air” painting ever caught on.

After serving in the French cavalry as a horse trainer, Renoir was almost summarily executed for suspicious activity. Returning to his comforting habit of plein air painting after the conflict, someone decided that he was using his easel as a cover for a spy operation. The young war veteran and Impressionist painter was taken into custody.

He spotted an officer whom he had once saved from a similar situation, now in power to save his life. Ironically, he had once allowed the young man his extra easel to impersonate as an artist when authorities were trying to round him up, and the disguise had worked. Now being marched to the firing wall, the officer could return the favor. He snatched Renoir from the jaws of certain death and obscurity. No turn goes unpunished they say, and the gallant officer was murdered soon after. With all this deadly intrigue, it is a wonder that “plein air” painting ever caught on.

Still, with all the lessons so painful

and costly, Manet was unbroken. He snarled that the only leader

worth following was Gambetta, a radical publisher now considered a “persona non grata.”

Cornelie, Berthe Morisot's mother, gasped at his statement, “When

you hear talk of that sort, there's no hope for the future of this

country!”

Cornelie's words would prove out... but

not without her daughter helping to birth a great art movement first.

A major influence to the origins of

Impressionism, Frederic Bazille

portrayed himself as ... a lefty.

L@L Frederic Bazille

Monet's close friend, fellow artist and sometimes financier Frederic Bazille was killed in the war. Bazille was from a wealthy family and always managed to provide for the two of them, even after Claude was married and had a child to provide for. It was Bazille who doctored Monet when he was nearly crippled in a freak accident while painting plein air. A true innovator, like a professional doctor he put Claude's leg into suspension and then painted him while lying helpless in the contraption.That is right-brained behavior.

Bazille was tall, strong, humble, diligent, and faithful. He was immensely talented, and his style of painting helped set the direction of the new art movement. Most of all, being a lefty, Frederic was what Monet was not, a problem solver. So Frederic Bazille was the very best friend and art companion Monet could ever have. But Monet was unhealthily dependent on Bazille, and unmercifully siphoned off of his generosity. When in trouble with his finances, unable to pay his rent or feed his family, he would lay an unreasonable guilt trip on Bazille, who always came to the rescue. Unlike most of his narcissistic associates, Bazille always answered the call to duty to friends or his country.

L@L Camille Monet who should have been made

a saint, right along with Joan of Arc.

When Monet's artistic soul-mate was killed while leading his fellow warriors in a retreat down a muddy road, the untimely death ended Monet's extended childhood. He seems to have absorbed some of Bazille's sterling qualities, and he morphed towards the man he needed to be.

He claimed the secret was to treat the horses just like he treated his models; let them do whatever they want, and pretty soon they will do whatever you want. Ever the cynic, he saw no glory in Bazille's sacrifice, to him his death was a symbol of the futility of the war.

The French were totally humiliated in the Franco-Prussian war, with Napoleon III exiled and the loss of their border provinces. Meanwhile France had to buy off the Prussians with millions of francs as a penalty in order to keep Paris from being destroyed. The wars and betrayals and losses were exhausting and disillusioning. The whole country needed a strong drink.

Men never pay much attention to the lessons of history, unless they are quite fresh. Renoir was philosophical, and hindsight had given him perfect vision... Courbet and his comrades were fools... idealists, suicidal... “They were madmen, but they had in them that little flame that never dies.”

NEXT: Go to innocence abroad

Men never pay much attention to the lessons of history, unless they are quite fresh. Renoir was philosophical, and hindsight had given him perfect vision... Courbet and his comrades were fools... idealists, suicidal... “They were madmen, but they had in them that little flame that never dies.”

NEXT: Go to innocence abroad

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for sticking your finger into the fire...please drop your thoughts into it!